1880s - Renaissance Revival

During the second half of the 19th century, both architecture and objects were inspired by a variety of historical styles. Gothic Revival, Renaissance Revival and Rococo Revival are examples of styles that will be referred to as revived styles. The dominant style among the new styles is the Renaissance Revival

This is a style strongly inspired by the classical design of the antiquity, which in turn is seen as a sort of baseline style. International magazines spread awareness of the new ideal, and in Sweden architects find inspiration in Europe's large cities.

The Swedish economy is booming and industry is beginning to flourish.. For cities, this is a period of rapid development. New businesses and industries are emerging and the rural population is largely becoming urban dwellers. This leads to extremely unhealthy overcrowding Residential construction is taking off and Stockholm is experiencing a building boom. The connection between the building boom and the prevailing style ideal means that Renaissance Revival becomes the dominant style among the city's buildings. For those who can afford it, there is a way out of the city's unhealthy housing. New transport connections, such as trains and ferries, contribute to the development of popular areas around our coasts and archipelagos with large villas as summer resorts for rich families. Taken as a whole, this means that the architectural style ideals take on different parallel expressions during the decade depending on the location and needs, and the summer nights reflect what came to be known as the Swiss style.

Thanks to industrial development, most buildings in the 1880s are constructed with prefabricated components. Balconies, stairs and railings are factory-made, just as carpentry and doors. Architects and builders can use pattern books and product catalogues, known as price guides, to pick the items that they like.

Stylistic expression of the façades

In the cities, Renaissance Revival façades are constructed with symmetrically placed windows and entrances. The façades are decorated with formal elements inspired by the ideals of antiquity and the Renaissance, including pilasters, columns, cornices, segmental arches and pediments, as well as smaller details such as acanthus ornaments, mascarons and volutes. The degree of decoration marks the status of the house and each floor gets its own character. At street level, the façade tries to imitate carved natural stone blocks and with the upper floors having the more lavish apartments with rich façade decoration. Finally, the top floor has simpler decoration, lower floor height and windows. The façades facing the courtyard are not decorated at all. The windows (link) have large openings that are slightly recessed into the wall life. These are usually designed with crossing central and transverse muntin and four outgoing arcs. The façades are plastered in calm, light, somewhat faded colours, such as a yellowish beige or white or a greyish white with the plinth painted in a stone grey colour. The window trim is painted with paint from linseed oil in dark, nut brown or dark grey-green colours. The roofs are made of folded sheet metal which is either black or red.

The entrance to the houses are very decorative even where the rest of the house is more modestly decorated. The entrance gates have strong, beautiful wooden paired doors with thick, polished glass. The stairwells play an important role in welcoming visitors and are adorned with marble imitation walls, panels, decorations and stained glass. The materials used match the status of the building.

Contemporary villas are constructed with panels in both upright and horizontal forms and lavish hardwood joinery. The façades are adorned with glass verandas which, like the paired doors and windows, are preferably fitted with coloured and patterned glass.

Beautiful façade at the junction Junfrugatan - Karlavägen in Stockholm, built in 1885.

Residences of the 1880s

Apartment buildings are often constructed in different sizes within the same building. The larger apartments with several reception rooms are primarily located in the houses facing the street whereas the courtyard houses have smaller apartments for large working families. In addition, working-class families often house lodgers in their already cramped apartments as a way of supplementing their household funds. In addition to overcrowding, class differences are also evident in the standards of the apartments. The apartments are primarily supplied with water from a well in the courtyard or cold water from a kitchen tap. In the kitchen, food is cooked on an iron wood stove. The food is stored in a pantry and the items that need to be kept cool are in an icebox. Toilets are most commonly outdoor toilets in the courtyard or in the back garden if you are a homeowner. In a lavish apartment building, the toilet may be located adjacent to the stairwell. Bathing is done in a tub and laundry is washed in a large pot on the iron stove. Heating comes from a masonry heater or a fireplace and homes are lit by candles or kerosene lamps.

Dining room in typical Renaissance Revival style from 1884

The interiors of the homes are strongly influenced by the fashion of the time and, according to the ideals of the time, were supposed to be dark. In the homes of the bourgeoisie, the better rooms are decorated in certain new styles, and this has been the case for a few decades. The dining room, the most important room for the bourgeoisie and a popular room for the whole family, is decorated in a Renaissance Revival style with dark colours such as nougat brown, ochre and dark red. Walls are covered with high panels and wallpaper. Ceilings are richly decorated with both stucco mouldings and ceiling rosettes in several colours.

Floors are usually made from floor boards. The room is furnished with dark wood furniture. There will be a dining table in the middle of the room which is crowned by a large chandelier. In some cases, there are also fixed cabinets and decorative objects, brass lamps, photographs, green plants and velvet textiles in the windows.

Reception room from the 1880s. Note the patterned carpet covered by another carpet.

There will often be a piano next to one of the walls where the children or a hired pianist plays for the guests. The reception room is decorated with a lighter colour scheme, groups of elegant sofas and chairs and sofas with curved legs. The entrance hall and the gentlemen’s room are dark and cosy, preferably oriental or Nordic in style, with dark wall panels, while bedrooms and nurseries have whitish woodwork and floral wallpaper. High double doors are installed between the reception rooms, while doors to private, simpler spaces are single doors. In smaller homes, one room can serve several purposes. This is particularly evident in the kitchen, which in many cases is used as both a living room and a bedroom.

1890s - Genuine and precious materials

The 1890s are characterised by the architects' desire for new stylistic expressions. It was said that the apartment buildings of the 1880s were of low technical quality and over-decorated with plaster ornaments without function. The sense of the material that the plaster was supposed to imitate, that is stone, had been lost. Instead, honesty and authenticity in the materials and architecture is in demand. New aesthetic values emerged, certainly with historical styles such as Gothic, Renaissance and Baroque, but they were combined in new ways. The influences are drawn from 15th and 16th century French châteaus and from the Danish Christian IV style.

The 1890s is a time of expansion in Swedish industry. The boom helps to pay for hospitals, schools and culture. Large areas of cities are appearing with both residential and industrial buildings. Commercial buildings are erected while new means of transport contribute to the emergence of the first permanent areas of detached housing. In small and medium-sized towns, large detached houses are arranged in central neighbourhoods for the local upper classes and working-class shanty towns are built around mills and industrial communities. The availability of cheap mass produced timber is a crucial aspect of residential architecture.

The stylistic expression of façades

The architecture of the 1890s is largely a revolt against the style of the 1880s. Rather than symmetrical façades, they are designed asymmetrically with differently shaped windows positioned according to the needs of the rooms, a novelty that creates completely new manners of façade architecture. Great care is given to imaginative roof silhouettes with both towers and gables projecting above the cornice, as well as wrought iron and cast iron decorations on balconies, anchor ends and tower spires. The façades are constructed using "real materials", which means that bricks and natural stone are visible and structural details such as arching over windows are highlighted with natural stone. Both windows and door are placed irregularly on the façade. Often, both straight and arched window lintels can be found on the same house. The joinery is painted in a dark tone, such as brown, reddish brown or green. Roofs are made of painted sheet metal or slate. The stairwells are richly decorated and now feature inspiration from medieval settings with popular features such as cross vaults, Gothic pointed arches and quatrefoils

Corner Storgatan-Torstenssongatan in Östermalm, Stockholm. 1890s

In the architecture of detached housing too, the architects' desire for authentic materials and asymmetry is demonstrated by varying heights, prominent structural details and a variety of roof designs. In northern and central Sweden, houses are usually built with wooden façades with both vertical and horizontal boards, while brick façades are common in the southern part of Sweden. The façades follow the architecture of the apartment buildings with towers and pinnacles and are adorned with wooden decoration on glass-covered porches and gable ends. Coloured glass panes in windows and verandas are popular. Houses are often painted in a light linseed oil colour which is darker around windows and then darkened still further at the window frames. Popular are yellow façades with brown mouldings, or a combination of green and grey.

Residences of the 1890s

In the 1890s, some important modern features are introduced in new exclusive residential buildings. The truly expansive apartments and villas have a space for a separate dry toilet and also for a bathtub . Now electricity is also making its entrance, with domes of pattern-blown glass spreading light in selected places and rotary lamp switches. But for the vast majority of people, outdoor toilets in the courtyard, shared baths and lighting by brass or glass kerosene lamps are still the norm. Towards the end of the decade, lifts are installed in the most lavish apartment buildings, changing the previous status distribution of the floors.

New villas are fitted with kitchens and living rooms just as apartments in the city. Life in detached houses is very different depending on which social class you belong to. For the working population, many people live in a limited space and a detached house is in fact divided into several apartments to be let. However, when compared to apartments in the city, the living conditions are much better given that there is a garden making it possible to grow food for own consumption. The villas are designed primarily for a comfortable family life rather than representation. This is quite natural as the owners prefer to live outside the city and have voluntarily refrained from the occasional social gatherings and visits.

Just as in the 1880s, the decorations of the homes of the 1890s are dark with the better rooms in pre-determined revival styles. The fixed furnishing is site-built but mass-produced. In the catalogues of various manufacturers, you can choose products in a variety of styles at an affordable price. Floors, joinery, wallpaper, ceilings and doors are designed to form their own coherent groups of rooms. Rooms are heated by masonry heaters and furnished with furniture of different styles, heavy tablecloths, plush and draperies and green plants on pedestals. Beadboard is popular in kitchens.

Window from the 1880s

The design and layout of windows is usually a good guide to the age of a building. The size, design and positioning of windows is one of the most important elements in the expression of both façades and rooms. The design of window profiles has a major impact on the distribution of light in the room A profiled moulding gradually guides the light into the room.

In the 1880s, windows are divided with central and transverse muntin. The two upper panes are almost square, while those below the muntin are larger, rectangular. The transverse mullion is needed to support the large panes of glass through the slender arches made of heartwood. The windows consist of single-glazed outward-looking glass that is closed by means of a hasp and tail hook. During the cold winter months, windows are supplemented internally by loose inner frames that may be sealed with adhesive strips. One interior window per room is hinged to allow ventilation. The window trim is painted with oil paint in darker colours such as brown or grey-green.

Windows of the 1890s

In the 1890s, unlike in 1880s, different window shapes are used on the same façade. The windows typical of the 1890s a central and transverse mullion. Below the transverse muntin there are two arcs while above the it there might be an complete arc. This is either with an arched top, or a straight one. Also typical of the period is the design of the lancet windows in a Gothic style. The joinery is ornate and, together with the large glass surfaces, lets in an abundance of daylight. Just as in the 1880s, the windows consist of outer and inner arcs. The inner arcs are removed in spring for better weathering and more light and refitted in autumn. Towards the end of the decade, the coupled window was introduced, but it would be some time before this became commonplace. The new coupled windows are closed with espagnolettes. For apartment buildings, the joinery is painted in dark shades of brown or grey. The colour scheme of the detached residences is based on contrasts between the different colours of the arc and frame as well as the lining.

Entrance doors of the 1880s

Entrance doors and door frames have a major impact on the status of the building and it is important that it is incorporated into the pattern of the rest of the façade. In the 1880s, the entrance door is artfully designed as a large wooden double door with glazed upper parts and an upper window where the door surround is painted in gold. The glazed sections are important because they allow the important daylight into the stairwell. The glass is sometimes etched with motifs ordered from the glassmaker's catalogues. Stylized urns with flowers and leaves are particularly popular . The entrance door leaf is decoratively worked with classical ornaments such as egg-shaped mouldings and its lower part have carved inserts. Wooden entrance doors are painted in a dark colour, preferably brown. The entrance doors are opened by means of a wooden or brass handle on iron or brass brackets.

Entrance doors of the 1910s

Entrance doors of the 1890s show a lot of variations depending on the style that the architect has used for inspiration. The entrance door is often asymmetrically fitted in the façade and the interest in authentic materials is reflected by the fact that the surround is made of stone. The entrance door itself is a paired door of varnished wood with an upper window with rounded arcs that lets daylight into the stairwell. The door leaves open inwards and have window panes. The enormous interest in wrought-iron details is expressed in decorative grilles, positioned to cover and protect the window panes. The bottom of the door leaf has carved decorations. The handles are often short and sturdy brass with a welcomingly designed.

The entrance doors of detached houses are usually double doors opening outwards and supplemented by a further set of double doors inside. The double door is designed with three inserts of which the top one usually is a glass pane. It is often made based on carpenters' pattern books and painted in linseed oil paint with rich colours, such as dark ochre, brown umber, English red or chrome oxide green. Door handles are pear-shaped with separate brass key plates.

Stairwells of the 1880s

Throughout history, the stairwell has had a central function as a welcoming hallway and at the same time confirming the visitor the status of the occupants of the house. This space is for a long time an important means of architectural expression but over time has taken on a secondary role.

During the era of Renaissance Revival, the craft of imitating precious materials was highly valued. Walls are decorated with segments framed by mouldings or columns in a variety of materials. In the most exclusive stairwells, the floors, walls, ornaments and decorations are made of real marble and joinery from precious wood. Different coloured stones are combined, mainly from Italy, such as white from Cararra, yellow from Siena and red Rosso Brocatello from Verona. It can also be sourced from Central Europe, such as a green-black with white pattern from Vert de Mer, black from Port d´Or and red Rouge Royal from Belgium. The popular green Kolmård marble as well as limestone, granite and sandstone are all sourced in Sweden.

Less lavish stairwells strive for the same stylistic expression through illusion-painted walls using scagliola and grisaille techniques. Woodwork is vein-painted to achieve the feel of more expensive woods, usually oak or mahogany. In the simplest stairwells, the walls are painted with a dark wainscoting and a border.

The ceilings are richly decorated with stucco decorations painted in rich colours and never in white. Stencilling in red, green, ultramarine, brown and gold is popular. Popular patterns such as the meander border and the flower vine were taken straight out of pattern books.

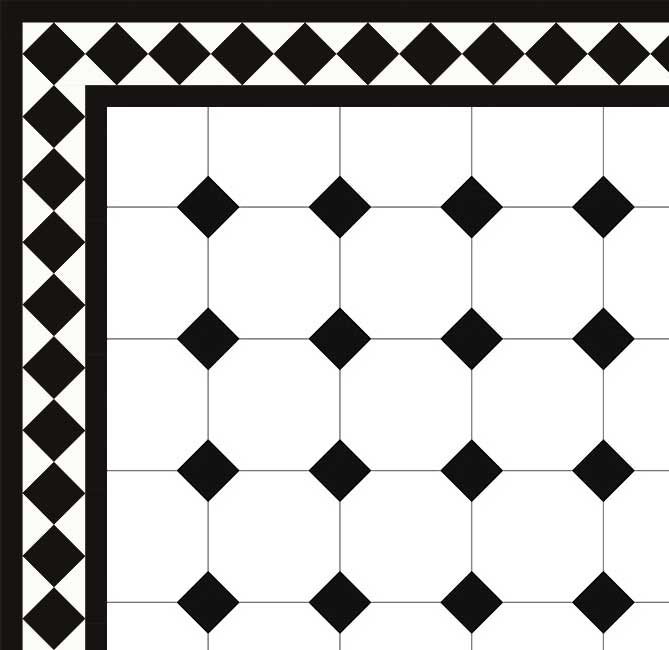

Floors are made of marble or limestone in different patterns. Ceramic tiles are now also becoming widespread. Tiles are laid in colourful geometric patterns, preferably in a star pattern, with a dark fringe around them.

Stairwells are either bricked with limestone slabs or a cast iron stairwell. Posts and railings are richly decorated and painted in black or other dark colours. The various types can be selected from the catalogues published by foundries. Along the walls are round wooden handrails with turned ends and cast-iron brackets. The handrail inside the front door, in the entrance hall, is often somewhat more sturdy and more profiled.

The stairwell has painted or glazed windows offering the necessary light while blocking the view of the courtyard.

Usually the ground floor consists of the main entrance to the manor and a smaller entrance leading to the kitchen, used by servants and messenger boys. In truly lavish buildings, there may even be a completely separate stairwell for the servants. On particularly large apartments, the entire wall may be covered with wood and glass panels that let the sought-after light into the apartment. Doors to the apartments consist of double doors, often with decorative lintels, and three inserts, one of which is glazed. Doors to kitchens or apartments in simple residential buildings are simple infill doors. The doors are dark-grained or vein-painted in oak, walnut or mahogany. The doors have black painted wooden handles, brass fittings and a bow around the door handle. Below is a separate key plate. At the side of the door, on the door lining, there is a bell.

The stairwell is illuminated by gas lighting. There is often a lantern hanging from a rosette on the ceiling. There may also be lanterns on the wall.

Stairwell, 1890s

The mix of styles in the 1890s is reflected in the design of the stairwells, especially in lavish houses. There are now stairwells inspired by medieval settings with popular features such as cross vaults, Gothic pointed arches and quatrefoils. However, many of the similarities with the stairwells of the 1880s with marble-painted walls, vein-painted joinery and lavishly decorated roofs divided into cross vaults, star vaults and coffered roofs. The entire stairwell is like a well-composed composition, creating its own world of shapes and colours. In simpler stairwells, the walls are painted with a dark wainscoting, border and an upper segment in a lighter colour. The ceilings are painted in off-white and have plaster mouldings (stucco).

The floors are laid in patterns of different types of marble, English tiles or red and grey limestone Terrazzo is now also more and more common. It can be cast in situ or laid as cement mosaic tiles and is used in stairwells as a cheaper alternative.

The apartments in lavish buildings can be accessed from the ground floor through full-height French doors letter boxes and high, richly decorated door crowns in plaster or wood. Doors to kitchens or apartments in simple residential buildings are simple infill doors. All of it including the lining stained in the same dark shade. The door leaves usually a section of etched glass, the format and pattern of which are ordered from the glass manufacturers' catalogues. Door handles come in many varieties but are usually cone-shaped in metal or black wood with a metal knob to finish the push. Electric bells are installed.

The lift is the great novelty of the stairwell of the 1890s. The lift also helps make apartments higher up popular. The lift shaft is placed in centre of the stairs and is made of wrought iron with a grating, which creates transparency.

Electric lighting starts to be installed in houses facing the street. The light is exclusive and the lanterns are decorated in glass and wrought iron.

Lamps and lighting from the 1890s

Until the early 20th century, Swedish homes were largely lit by daylight. After dark, light was provided by wax candles, candlesticks or oil lamps, and for those who could afford it, kerosene lamps were also available from the 19th century. In the evenings, family members would gather around a light source and only at parties would the whole home be lit up. Towards the end of the 19th century, the city's property owners are required to install gas lamps on their houses in order to create light in the urban space. This is also when the first electric start appearing, initially for use in workplaces and shops to reduce fire hazards and improve working conditions.

In the 1890s, the most common sources of light in the home were brass or glass kerosene lamps. The homes of the rich start getting electricity changing life for the residents. Cupolas with pattern-blown glass spread the light. As a guide, in 1912 had 22% of residents in Stockholm electric lighting. Ten years later, the figure is 80%. However, it took much longer to reach farms and homes in the countryside.

In homes, electricity is initially mainly used for ceiling lighting. The light points then slowly grew in numbers. The first electric floor lamps around the year 1900 are rather sturdy constructions in cast brass, turned wood or wrought steel.

The electricity wires are visible and made from twisted textile cords attached to porcelain insulators in the ceiling and walls. It is only by the 1930s that they start being hidden inside the walls of city apartments. Conduits in the walls are made of porcelain pipes. All switches and sockets are surface-mounted and mounted on plates. They were originally made of white or black porcelain. Switches are of the rotary type where you switch on and off by turning the switch.

Around the turn of the century, both wall and ceiling lamps were often fitted with a wooden plate as a spacer to provide space for the connection between the knob lead and the lamp. These plates are found used well into the 1920s. The wooden panel could be either dark brown or painted the same colour as the wall.

Light fittings were installed in the doorways of apartment buildings. The first ones consist of a simple bare bulb but evolve into a glass lantern to reduce glare.

In the late 19th century, it became common to antique paint brass to make it look older. In the early 20th century, bright brass is again popular, while the dark tones become popular again in the 1910s and in the 1930s and 1940s.

Floors of the 1880s and 1890s

The floors are usually made of pine or spruce flooring with staggered joints and fixed or loose springs. There is often a slightly wider edging board along the walls. The floors can be scrubbed or varnished or painted with linseed oil paint. Many floors are meant to be covered with linoleum flooring, which generally means lower quality wood and installation.

The linoleum flooring (also called cork flooring) will become very popular in the 1890s. The flooring is exclusive and can be laid over the entire room floor or as a smaller carpet. Often, many different colours are used to they imitate real carpets. The printed pattern is often parquet imitation, floral or textile pattern.

In the latter part of the 19th century, oak parquet began to be produced in joineries and became popular in the dining room. However, it has long been used in manor houses. The parquet comes in finished squares, often with geometric patterns of stars, squares or diamonds. The floor is given a shiny finish by waxing and polishing. Parquet flooring is also used, mainly in living rooms, by nailing small pieces of wood to a board substrate.

Just as for the stairwells of apartment buildings, the entrances to lavish villas are fitted with tiled floors based on English models, known as Victorian floor tiles.

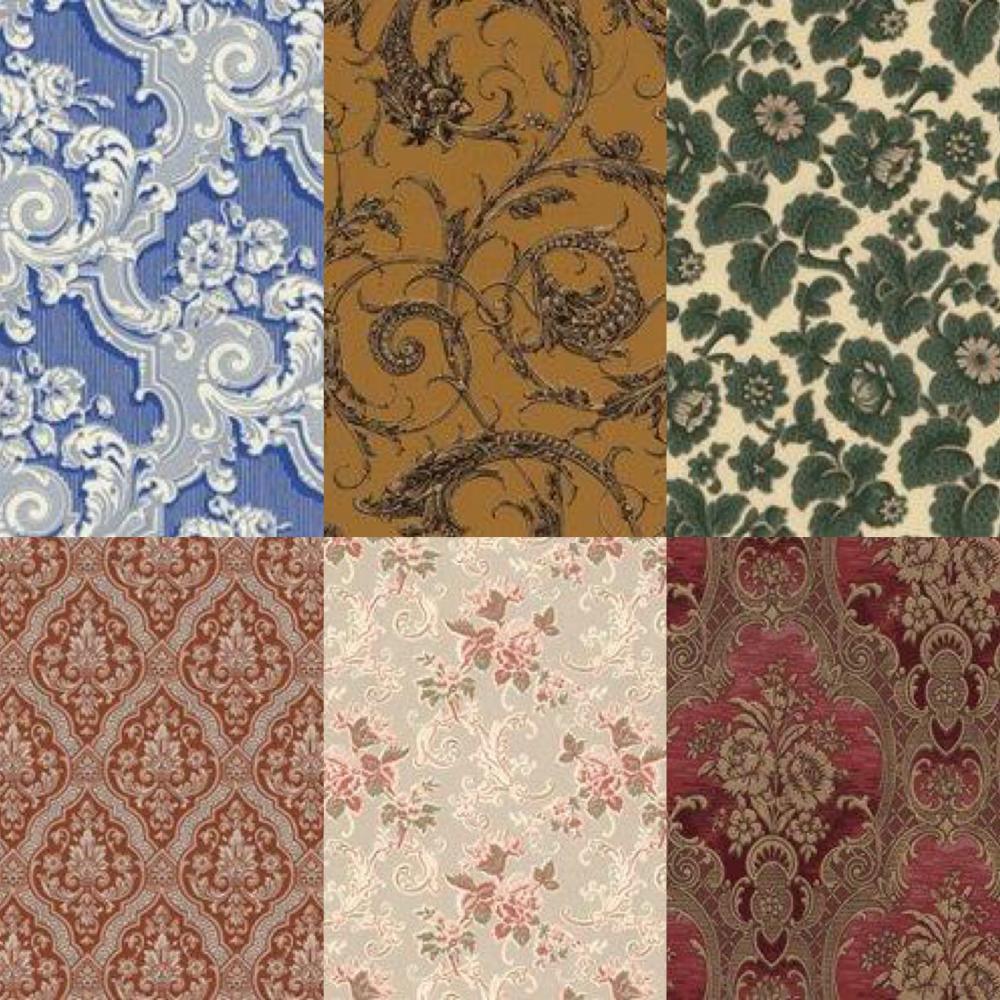

Wallpaper of the 1880s & 1890s

Towards the end of the 19th century, wallpaper with wild, seemingly unstructured floral patterns start to dominate. These are mostly imaginary flowers.In addition, wallpapers with textile imitation are popular. At first, dark background colours dominate, but towards 1900 they become lighter. The most popular base colour of the 1890s is light cream, which looks beautiful against dark patterns or bright colours like red and blue.

Walls have wallpaper that fits the different types of rooms. In the dining room, the high panel will be complemented by dark wallpaper following the Renaissance Revival ideal, often of large floral in strong colours such as red, green, gold and black or imitation golden leather wallpaper.

The walls of the reception rooms can be lighter pastel colours with gold, silk or other imitation textiles. In the master bedroom, the oriental style is popular, with motifs from exotic cultures such as Japanese cherry branches or woven patterns from oriental carpets.

Floral wallpapers are often chosen for the bedroom. In the hallway is, for example, oak-grain wallpaper or imitation wallpaper used. Where kitchens are wallpapered, they can be patterned with geometric designs, wood or tile imitation. They are often varnished to make them easy to clean.

Examples of wallpaper from the late 18th century, Glue and Handprint. You can also find them in our webshop under "Wallpapers".

Joinery of the 1880s and 1890s

For centuries, mouldings have been used to cover joints between different parts of a building. The joinery has been gratefully designed to enhance the stylistic ideals of the time. In the 1880s and 1890s, panels of different heights and different designs were used depending on the function of the room. In the dining room and hallway, the highest panel is placed with heavily profiled inserts and a final narrow shelf for ornaments. In other reception rooms, it is popular to use a floor plinth (three-piece floor plinth), about 3-4 cm high, consisting of a profiled plinth, a smooth board and a finishing profiled cornice. The simplest version of the floor plinth is large and richly profiled. The panels are painted in brown or ochre, or imitation wood to imitate oak or mahogany.

Below the windows there is cornice reaching to the window frame. The panel has frames and inserts that are painted in different colours. The window niche is also covered with panelling. The panels are all painted in the tone that is the starting point for the room's function and intended new style. Stairwells, halls, service corridors and kitchens are usually clad with beadboard with crown moulding. White painted mouldings are common in the kitchen and bedroom.

Door foot and cornice with dentil, a profile taken from classical architecture. These could adorn both doors and windows, inside and out.

Stucco of the 1880s and 1890s

Mouldings, rosettes and other ornaments are produced in large quantities in the plasterer's workshop and installed on site. This craft arrives in Sweden in the 15th century and grows gradually. At the end of the 19th century, many formal languages were used simultaneously, depending on the purpose of the room. In the 1920s, the forms become simpler and more stylish.

The ceiling of the living room has a very important role in its character and great care is taken over its design. Here the ceilings are richly decorated, divided with mouldings and friezes into cool patterns that are decorated with paint, a far cry from today's white-painted ceilings. The shapes are adapted to fit the intended style of the room. The ceilings of the dining rooms have a more austere Renaissance Revival in a dark colour scheme, while the undulating Rococo Revival ceilings of the drawing room are lighter, though not white but rather pastel with hints of gold.

The ceilings are framed by stucco mouldings with classical motifs such as acanthus leaves, flower garlands and urns. A ceiling rose with a hook for chandeliers with candles is placed in the middle of the ceiling. In addition to its decorative function, it also has the important function of protecting the flammable ceilings from candles and kerosene lamps. In kitchens, bedrooms and halls, there are often simpler ceilings with hollow corners, in other words plastered rounding between wall and ceiling. Kitchens might have beaded ceilings.

The roof rosettes were large and expansive. The most ornate examples were found in the suite with reception rooms, which in apartments always faced the street.

Doors of the 1880s and 1890s

Until the mid-1930s, doors are designed with frame and infill, although towards the end it is in a rather simplified version, from wooden frames with planed profile to veneered laminated wood or wood fibreboard. The appearance of the door inserts and profiles had a major impact on the design of the dwelling, and the door impressions are also an important part of the overall impression.

The interior doors of the 1880s and 1890s consist of heavily profiled prefabricated solid wood infill doors. The customer can freely choose the design and number of inserts from illustrated catalogues. Access to the reception rooms are via large double doors, preferably with high decorative lintels of carved wood or plaster. These are chosen with care for the specific functions and style of the rooms. A popular door type has two high rectangular inserts and a narrow one in between. But there are also other variants, including squares. Single doors with four vertical and one horizontal insert lead to the private area of the home, such as the kitchen and bedroom. The doors are usually opened with conical door handles made of black painted wood with a small knob at the end and brass fasteners and separate small round key plates. There are also simple cam locks.

The doors were surrounded by door skirting with heavy profiles and finished with skirting boards along the floor. Many door sections, including lintels, that are now painted white were originally in an imitation wood.

Fire places, 1880s and 1890s

In the bourgeois home of the 1880s century, rooms were furnished with masonry heaters of different shapes in the style of the room. Lavish decorative masonry heaters are placed in the living rooms while simpler ones are placed in the bedrooms. In the hallway, the tiled stove is often adorned by a mirror. The different parts of the masonry heaters can be freely selected and combined together according to taste using the manufacturers' price lists. Palmette leaf, urns and shell shapes are some of the popular decorations. Masonry heaters in the Renaissance-style are characterised by dark tiles with relief patterns. They may have small square bowl-shaped tiles, masonry tiles, often in green or brown majolica glaze. However, white smooth masonry heaters with ornate crowns, either circular or rectangular in shape, are placed in simpler rooms and among the commoners, workers and servants. Masonry heaters could also be covered with a relief pattern.

At the end of the decade, the historicizing styles are criticized and instead "authenticity" is prioritised, which means that the Swedish 18th-century masonry heater with tiled feet and chamfered corners becomes the model.

Kitchens of the 1880-1900

Life in the kitchen of the late 19th and early 20th centuries is quite different from our kitchens today, both in terms of how we use them, but especially from a technical point of view. In workers' housing, the kitchen were you gather for cooking, socialising and sleeping. It is not uncommon for the whole family to live in the room, including a lodger. Here, people gather around the wood-burning stove, or the masonry heater with its heating cabinet, and around the room there may be a cupboard or open shelves for utensils.

Life in lavish apartments and villas is different. Here, the kitchen is a clean workplace with its own exit so that the kitchen staff, servants and sometimes even the children of the household do not use the entrance. The owners does not set foot in the kitchen and in order not to be disturbed by all the rattle and noise, the kitchen is always placed towards the courtyard, or to the north, as far away from the better rooms as possible. A service corridor leads from the kitchen to the dining room. The servery includes tall, beautifully built-in cabinets with base cabinets for larger utensils, drawers for cutlery and overhead cabinets for crockery, glasses and terrines. There may also be a small work area for storage and a small sink area.

Inside the kitchen, however, pots and tools are on open shelves or hooks. Food and condiments are placed in a pantry, often made of beadboard, which faces the outside wall with either a window or a vent, which is a way of keeping the space cold. In the kitchen, or in a nearby room, there is also an icebox to which the iceman regularly delivers ice blocks.

Food is prepared on a low counter and workbench with a lower cabinet and a top made of Carrara marble. The marble is an excellent base for handling food and after dinner, utensils and crockery are washed in a basin on the bench, which may explain its low height. Along the sink is a splash guard which, like the top, could be made of marble or zinc. If the bench is only used as a workbench, it is often wooden, or possibly oiled. There is a sink in the kitchen but this is only used as a drain. The sink might be surrounded by a zinc sheet or enamelled cast iron.

In the 1890s, the kitchen are commonly fitted with a high wall-mounted cupboard, like a sideboard. The cabinet opens with a key and has wooden knobs as handles. Like the workbench base cabinet and the serving aisle cabinetry, the cabinet is designed in solid wood with profiled half-French doors painted with linseed oil.

The heart of the kitchen is the wood-burning stove, and tiles with bevelled edges and without grout are placed around the stove, and if it is extra lavish, the tiles can also be fitted with borders and pilasters. (The gap was sealed with chalk, pigment and water and later with white tile grout.)

The kitchen has a lower status than most other rooms, and while the reception rooms are furnished with lavish woodwork and decorations, the kitchen is made easy to wipe and keep clean. The walls can be plastered, but it is particularly popular to cover them and the ceiling in beadboard. Some even choose to put up wallpaper. However, the woodwork is painted in the same colours as the rest of the home. Emulsified painting, varnished to a glossy, easily dried finish, is common from the late 19th to the turn of the 20th century.

Hygiene 1880-1900

In the second half of the 19th century, daily hygiene consisted of washing hands and face with the help of a washbasin. People rarely bath and when they do, it is in a tub on the kitchen floor. For those who do not have indoor running water, water is taken from a well in the courtyard and heated on the stove. With technological development, cleanliness and dirt will become a clear dividing line between rich and poor. For those who can afford it, a small washroom is arranged within the home, called a toilet, which has a sink and dressing table. At the end of the 19th century, some of the poshest homes started getting their own bathtubs, and in villas these started to be fitted in the cellar. The bathtub is free-standing cast iron with feet that might be shaped like both lion paws and bird claws. Washbasins often have a separate hot and cold water tap. They are deep and have a raised rear edge to protect against splashing water. Until the 1940s, taps often had a porcelain button with the text hot or cold. The room is decorated with ceramic tiles, limestone or marble floors. The walls are covered with beadboard or tile and the details are made of brass.

For most people, having their own bathroom is a luxury that is almost unimaginable. Their reality remains the tub in the kitchen, or possibly a communal bath in the basement of the apartment building.

Dry toilets are located in the courtyard, attic, or if you belong to the bourgeoisie, there may be a dry toilet within the home or in the stairwell. Fashionable apartments start to be fitted with water closets around the turn of the 20th century.